Welcome to the first of our episode-by-episode examinations of Falcon and the Winter Soldier. A minefield’s worth of spoilers lie ahead, and Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Avengers: Infinity War (2018), and Avengers: Endgame (2019) will all prove pertinent to events we’ll see in episode 1 of this series.

“How does it feel?”

“Like it’s someone else’s.”

“It isn’t.”

The it in question is the iconic shield and symbolic mantle of Captain America, passed on at the end of Avengers: Endgame from Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) to Sam Wilson (Anthony Mackie), and the words — literally the first we hear in Falcon and the Winter Soldier — serve as a kind of thesis statement for what this series is all about.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has had its fair share of swings and misses — me personally, I find the movie versions of the Guardians of the Galaxy near unendurable, and don’t even get me started on Thor — but one thing the MCU has done almost all the way right is its treatment of Captain America.

In the Marvel Universe of the comics, Steve Rogers, a.k.a Captain America, is the hero. The hero’s hero. The gold standard against which all such things are measured. The bravest and the best. Like a Lancelot or a Galahad, the superiority of Captain America’s ability is a direct result of his superiority of character. Consider the comic series Civil War (2006), which largely provided the source material for Captain America: Civil War. In both comic and movie, the heroes aligned with Tony Stark are believers in a governing system that may be flawed, but nonetheless provides the only reliable framework for dealing with super-humans and the potentially negative effects of their actions. The heroes aligned with Captain America, on the other hand, are believers in the cult of Captain America. Policy has nothing to do with it, isn’t even part of the argument. If Captain America’s not for it, they’re not either. Simple as that. Case closed.

In a world where grown-assed men have been known to burst into reverential tears at the mere sight of Captain America, it’s not hard to see how the two people closest to the man and his legacy would feel unworthy of filling his shoes. For Sam Wilson and Bucky Barnes, the title characters of this series, their proximity to Steve Rogers has enhanced his legend rather than dimmed it.

Lest anyone labor under the delusion that this series is some kind of introspective meditation on the nature of responsibility, the opening statement and title card are followed by an eight-minute aerial action set piece over Tunisia — featuring cargo planes, helicopters, wing-suited terrorists, machine guns, missiles, canyons, and our old friend Batroc (Georges St. Pierre) from Winter Soldier — that wouldn’t be at all out of place in the beginning of a James Bond movie. Director Kari Skogland, a veteran of high end TV (she’s directed episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale, The Punisher for Netflix, The Walking Dead, The Americans, and House of Cards, among others), knows her way around an action scene, and uses her big budget to good effect. The sequence is introduced with the concise immediacy of a video game: a criminal group called the LAF has targeted a military liaison for a kidnapping, and it’s up to the Falcon, who the US military is using as their own in-house super-hero, to stop them.

Sam has an intel assistant, a young soldier named Lieutenant Torres (Danny Ramirez), who alerts him to a globalist terrorist outfit calling themselves the Flag Smashers, who are dedicated to ‘a world that’s unified without borders.’ Sam tells Torres to keep an eye on them, and call him in if anything gets out of hand.

Back in Washington, Sam is part of a ceremony donating Captain America’s shield to the Smithsonian. A government official assures Sam that donating the shield is the right decision, but James Rhodes (Don Cheadle), a.k.a. War Machine, isn’t so sure, and wonders openly why Sam didn’t take up the mantle. There’s the merest hint of accusation there in Rhodey’s question: Steve Rogers gave the shield to you. He could’ve given the shield to the Smithsonian himself if that was the direction he wanted to go. He could’ve given the shield to Congress, or to the Stark Foundation, or just kept it in his garage. He didn’t do any of those things. He gave it to Sam Wilson, because he felt Sam was worthy of it, and while Rhodey seems to understand it, he can’t quite hide his disappointment that Sam is choosing to pass on the cup put before him.

The other title character of this series, James Buchanan ‘Bucky’ Barnes, is busy seeing his court-appointed psychiatrist — it’s a condition of his pardon — and denying the nightmares his past operations as the mind-controlled Winter Soldier have given him. We see one such operation in flashback, that ends with the murder of a young man who witnessed the Winter Soldier killing his primary target. Bucky is a haunted, lonely man, his friends and family long dead, his life twisted out of shape by decades of violence and murder. He’s kept himself occupied since Endgame in making amends to the survivors and victims (and, in one case, beneficiaries) of his time as the Winter Soldier, but amends are far easier in theory than in practice…and there may be some things for which no amends are possible. It turns out that the young man Bucky killed in the flashback has a father, Yori Nakajima (Ken Takemoto), still grieving over his son’s unsolved and unexplained murder. Bucky has developed a relationship with the old man, but understandably hasn’t quite worked up the nerve to tell him about his part in his son’s death.

Sam returns to his childhood home in Delacroix, Louisiana, to his family’s fishing boat and his sister who’s decided to sell the business. Sam attempts to procure a loan to save the boat and the business, but it seems not even an Avenger’s status and good reputation counts as collateral for the post-Blip banks. (Hard to believe that there wouldn’t be someone in the echelons of power who wouldn’t call up the bank and say, “You’re denying a decorated veteran and active Avenger a fucking small business loan? Are you high?” But I digress…)

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Torres, on the trail of the Flag Smashers in Switzerland, gets his ass stomped by a super-human terrorist while trying to foil a bank robbery. He contacts Sam with the video footage he took with his phone — Sam, perhaps troubled by the super-human angle, tells him for now to keep his Flag Smasher info on the down low — and no sooner has the call with Torres ended than Sam’s sister alerts him to breaking news on TV.

It’s the government official from the Smithsonian, “on behalf of the Commander in Chief and the Department of Defense,” ominously introducing “a real person who embodies America’s greatest values…someone who can be a symbol to all of us.”

Your new Captain America.

Oh, boy.

____

One of the reasons, I think, for the enduring popularity of Marvel’s heroes is that their creators and later caretakers were (and remain) devout, passionate believers in the ideals that made those characters heroes in the first place. Whatever else you might say about them, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were embarrassingly sincere about their ideas concerning fairness, equality, justice, bravery, and taking responsibility for the welfare of one’s fellow man, and they passed their zeal for these heroic qualities on to their successors.

The first black character in mainstream comics was Gabe Jones, one of Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandos, who made his debut in Sgt. Fury #1 (May 1963). Jones wasn’t a mascot, wasn’t a sidekick, but was a full and equal member in good standing, serving right alongside his fellow Commandos, which included an Irishman, an Italian, a Jewish kid from Brooklyn, and a southerner among their ranks. Stan and Jack were both World War II veterans. They knew damn good and well that black soldiers didn’t serve in the same units as white soldiers, and they certainly weren’t accepted as commandos. And more, I doubt the Marvel offices in 1963 were exactly inundated with letters demanding a larger black presence in their war comics.

Stan and Jack put him in anyway, and when the colorist got it wrong, assuming there’d been a mistake and coloring Gabe as a white man…? Stan and Jack made sure the coloring was corrected for subsequent issues.

A few years later, the first black super-hero, the Black Panther, made his debut in Fantastic Four #52 (Jul 1966). This character was noble, brave, and brilliant, the king of the most technologically advanced nation on earth. Decades later, I sat in a Cinerama in Seattle watching a movie bearing this character’s title, surrounded by a good many fans of color, some wearing dashikis and no few with tears in their eyes to see, at long last, a hero on the center stage who they could identify as themselves.

And I’m telling you, gentle reader…Jack Kirby, the co-creator of both Captain America and the Black Panther? He’d have loved it. He’d have loved it with every fiber of his being that these fans felt included, that the heroism and nobility of the Panther, a character he helped create, would resonate so powerfully with so many people…

…the same way he’d be saddened that the prospect of a black Captain America would still be seen as some kind of negative by so many people, in real life no less than the movies. A Captain America who’s eminently qualified, by the way: brave, capable, kind, and inspirational.

Sam being a black man doesn’t affect his status out in the field at all. Torres and the active military don’t care that Sam’s black; his capability and competence are all that matters when it’s show time. But back home, it’s a different story. Back home, though no one ever comes right out and says so, Sam’s blackness is an ever-present factor, the inescapable elephant in a claustrophobically small room.

It’s a factor for James Rhodes, who might be eager to for reasons of his own to see a black man carry the shield and wear the name of Captain America.

It’s a factor for the bank to which Sam and his sister apply for a small business loan. The bank doesn’t say they’re turning down the Wilsons because they’re black — the bank representative certainly doesn’t seem to see himself as any sort of overt racist — but would this same bank under otherwise equal circumstances really send white Avengers like Clint Barton or Carol Danvers packing? Maybe. Maybe not.

And it’s clearly a factor for the otherwise unnamed Commander in Chief and his Department of Defense, for whom a “real person who embodies America’s greatest values” clearly is not and never could be a black man.

____

Ask and ye shall receive:

- Captain America’s shield in the comics is a unique item, made of an alloy of vibranium and adamantium, two fictional super metals. The vibranium allows the shield to absorb and dissipate energy, while the adamantium makes it as close to indestructible as a man-made object is likely to get. Like Captain America himself, no one’s ever managed to duplicate the process that created the shield. Wakandan vibranium of the type in Captain America’s shield made its first appearance in Fantastic Four #53 (Aug 1966). Adamantium was first referenced in Avengers #66 (Jul 1969).

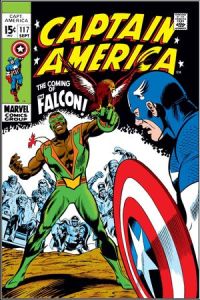

- The Falcon’s first appearance was Captain America #117 (Sep 1969), created by Stan Lee and Gene Colan. Sam Wilson has no military background in the comics, nor is he from Louisiana; he’s a social worker, born and raised in Harlem. Curiously, the Falcon didn’t actually fly until getting a winged flight apparatus courtesy of the Black Panther in Captain America #171 (Mar 1974); before that, he swung around town on a cable and grappling hook sort of number.

- The Redwing of the comics is an actual bird with whom Sam has an empathic / telepathic link. If Sam concentrates on it, he can mentally link up with birds other than Redwing.

- Bucky Barnes first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Mar 1941), created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. The current Winter Soldier version of the character was created by Ed Brubaker and Steve Epting, and first appeared in Captain America #1 (Jan 2005).

- Though he shares almost nothing with the character in the show other than the name, the first appearance of Joaquin Torres was in a photograph in Captain America: Sam Wilson #1 (Oct 2015); he made his first ‘in-person’ appearance in issue #3 of that series (Jan 2016).

- French mercenary and career criminal Georges Batroc — Batroc the Leaper! — is a classic Captain America villain who first appeared in Tales of Suspense #75 (Mar 1966). The Batroc of the comics is a little like a costumed French version of Omar Little from The Wire, in that he does what he does because he thinks it’s fun and it’s profitable, but is inclined to exclude innocent people who aren’t in the game. He’s most definitely a criminal, but doesn’t tend to be a murderous one.

- The Flag Smasher of the comics is a person, not an organization, created by Mark Gruenwald and Paul Neary. He first appeared in Captain America #312 (Dec 1985). The motivation given the group in the show, however, is roughly the same as the character in the comics.

- James Rhodes in the comics is a little more blue-collar than the character played by Don Cheadle in the MCU, but the essential traits are the same. Rhodes made his first appearance in Iron Man #118 (Jan 1979), created by David Michelinie and John Byrne. Not unlike Sam Wilson and Bucky Barnes, both of whom have worn the mantle of Captain America in the comics, Rhodes took a turn as Iron Man, beginning in Iron Man #170 (May 1983) and ending in Iron Man #200 (Nov 1985). He began wearing heavily weaponized Iron Man armor as War Machine in Iron Man #282 (Jul 1992).

- A title card in the credits confirms the new Captain America is John Walker, created by Mark Gruenwald and Paul Neary. Gruenwald described the character as someone “who embodied patriotism in a way that Captain America [Steve Rogers] didn’t.” We’d think of him now as a MAGA, America First version of a patriotic super-hero, with all that that entails. He first appeared as the Super-Patriot in Captain America #323 (Nov 1986), and assumed the mantle of Captain America by government mandate in Captain America #333 (Sep 1987).

Questions or comments, please let me know! Otherwise, I’ll see you all for episode 2!

2 replies on “Falcon and the Winter Soldier, Ep. 1: New World Order”

While I ended up enjoying the WandaVision story arc, I had a much easier time engaging with the early episodes of Falcon and the Winter Soldier.

I felt there was a lot of strong acting in the episode and am already a fan of Amy Aquino (the good Dr. Christina Raynor).

It has been interesting to see where the MCU bends the comic material to fit. I know you’re not a fan of Guardians and Thor, but I feel like MCU gets it right a good bit more than not.

And, probably sadly, where they miss for you, is probably hitting with the larger audience, providing the $$$ they need to continue. Thor, I know, was struggling until they took a lighter tone with him.

I’d totally be interested in reading a Thor script done by yourself.

I think the MCU bats about .500. What I like, I tend to really like, and what I don’t, I really don’t. Strangely, it’s not any lack of fidelity to the comics that tends to rub my fur the wrong way. The movies must and do exist on their own merits. Anyone who wants a comic book experience can just go read a comic book. So I’m not terribly bothered by MCU changes to characters and concepts except in those cases where I think it makes the characters and concepts less interesting. The Guardians have essentially all been reduced to the same character, with maybe one or two easily discernible physical traits to help you tell them apart. Star Lord is good-looking and dumb. Drax is green and dumb. Gamora is green and hot. Rocket is a raccoon. Groot is a plant. And that’s it. That’s what they bring to the table. I wouldn’t trust any of these halfwits to use the goddamn microwave oven unattended, let alone save the galaxy (and this is borne out by pretty much everything we see in Infinity War and EndGame, where the Guardians aren’t just useless, but are active detriments to any plan or accomplishment). And Thor? He’s pretty much Doug Heffernan from King of Queens in the movies. A dim-witted chubberoo living in a mental vacuum of junk food and unwarranted self-confidence. I mean, I’ll grant that’s kind of amusing, in a lowest common denominator, kick-in-the-nuts sort of way, but is it more interesting than being a God of Thunder and Prince of Asgard?

Most people do seem to like these Guardians and Thor movies. I confess, I don’t quite get it. The first Guardians movie is at least amusing. I don’t think it’s a very good movie — it’s just kind of all over the place — but at least it’s fun. Napoleon Dynamite as post-ironic super-heroes in space. But that second movie is a hot dumpster load of awfulness. I think it’s legit terrible. And the Thor movies are just bland, generic movie gruel, altogether lacking in drama, excitement, ideas, or thrills.

I couldn’t possibly do Thor better than any number of outstanding creators and writers have already done him: Jack Kirby, Walt Simonson, Jason Aaron, Don Cates, even Mark Millar and his alternate take in Ultimates.